Inside

the

Winter Issue:

Happy

Birthday Harry

and Season's Greetings

From The Circle Team

Harry

Chapin

Foundation Maintains

"Just Do Something"

Philosophy

Remembering

Harry:

A Collection of Rare Photos

Fan Fare

Hitting

All

The Right Notes:

An Interview With

Big John Wallace

Run-DMC

Star

Strikes a New Chord

With “Cat's in the Cradle”

Behind

the Song:

Cat's in the Cradle

Finally...

A

West Coast

Jen Chapin Tour!

Consider

These Ideas For

Giving Gifts With Meaning

This Holiday Season

DC's

Community Harvest

Strives To Provide

"Good Food For All"

Singer-

Songwriter

Lea Creates Positive

Energy In Music

and Action

Hitting All The Right Notes: An Interview With Big John Wallace

by Linda McCarty

|

|

Photo

by Mark Lamhut

|

In a recent conversation John Wallace remembers meeting the Chapin brothers at Grace Church, his days as the only member of the Harry Chapin band from its beginnings to the end and carrying the music and message on today.

Circle!: For those who don't know your musical background before becoming the first member of the Harry Chapin Band, can you tell us about first meeting the Chapin brothers?

Wallace:

We met at the Grace Church in Brooklyn Heights, where I was the boy soprano

soloist. Steve said there was an ad in the paper looking for choir boys.

I joined in '52 and Steve says we met in '55. Back then we weren't

friends because I was four years older, and he was a little kid. Steve

and I got close after we were in the boys choir in the alto section. As

teens four years didn't mean so much. We were all serious about the

choir and singing.

Harry wasn't

in the choir per se, but we became close as teenagers when Harry, Tom

and Steve had already started their band, The Chapins. I loved listening

to them. I was into doo-wop in the mid '50s, with all the harmony and

great vocal sounds. There was a mutual admiration even though it was different

cultures.

Later, when I had an upright bass, I'd go around with Harry in Brooklyn Heights to people's homes he knew and respected.

Circle!: Do you mean playing at parties?

Wallace:

No. It wasn't a party. It was just a singer-songwriter playing in

people's living rooms asking what they thought. Harry knew where

he wanted to go.

Harry looked

up to Steve for musical things. Harry had drive and will, but Steve is

more laid back. Harry was a true extrovert. [Harry's brother] James

said, "The difference between an extrovert and an introvert is that

an extrovert draws energy from a crowd, but an introvert costs energy."

Steve can be extroverted and sociable when he wants. Tom is more solitary

than the others and more self-contained. Harry was sociable but goal-oriented

and trying to do things to get himself along.

When I was

living in New Jersey and wanted Harry to hear a song, I'd drag him

over to my house to listen to a record. After couple of seconds, he turned

the TV on with the sound down, and when a commercial came on he would

change the channel. You had to work to get his attention. He'd talk

about going through life round-shouldered, avoiding things that would

get in the way.

But the

choir was a big deal for all of us. Harry was around it and it was focal

point for all of our lives. It was in their neighborhood. Mrs. McKittrick,

the choir director, had more power and influence over us than our families

did. It was pro gig and we got paid. It was a famous choir and highly

respected and a huge force for good in our lives. It was the glue that

held everything together. Steve was really close to her, more than any

other kid. He took organ lessons from her and worked in the library and

was indispensable there.

The pinnacle

of my career was when I was the boy soprano soloist there. It's rough

when your career peaks when you're 12. They give out two medals every

year, and I got one of those.

It was in

one of the choir shows that The Chapins were introduced. People singing

and playing instruments at the same time was not common then and it impressed

people. Harry was a serious banjo student then. I remember Tom walking

into a room at church at age 12 and fingerpicking the guitar. Even then

I thought he was good. By the time they were teens, they all were pretty

good and had a career playing around the area. They were on that track,

really trying to make it, and it was the [Vietnam] war that knocked that

apart a little bit. They were going to get drafted if they weren't

in school, so Harry went to college and things got fractured a little

bit. When he majored in architecture at Cornell, that's when he said,

"Not only could I not design a building, but I wouldn't know

what to inscribe around it."

But The

Chapins kept going on without him. It was Tom, Steve, Doug Walker, and

Phil Forbes, who was from the choir, too. Jim played drums in the beginning,

and they got a contract with Epic and did some demos. Somehow, they wound

up at The Village Gate. The show Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well And

Living In Paris was playing there, and they made a deal to get the

place for $400 a week at night after that show was over. Harry wanted

to get back in the group after he left Cornell and had new songs then,

including "Taxi." They said, ‘Start your own band' so he did.

Harry, Tim Scott, Ron Palmer and I opened for The Chapins. That's how Harry got discovered. He spent $800 of his own money to make a demo tape on open reel--this was before cassettes. He took it to 30 record companies, and got Ann Purtill from Elektra to come down to see him. And then he got a good review in the paper. There was a hijacking story on the front page, and after it said turn to another page to continue there was the headline, "Harry Chapin Sings Gorgeous Ballads." Harry put it on a sandwich board outside of the club. There were three people in the audience for first show. It was a few weeks' run, and then he was on his way to a record deal. After the bidding war between Jac Holzman of Elektra Records and Clive Davis of Columbia Records, Harry's contract with Elektra was the highest deal ever given to a new artist. From then on, it was Cinderella time for the new band.

Circle!: When the call came from Harry that he wanted you to sing with him, did you think he and his music had stardom potential?

Wallace: I never was a folkie the way he was. His heroes were Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and The Weavers. I was more into Ray Charles, R & B. I'd played in a band called The Sloptones with David Zenie, Charlie Buhler and Bobby Lamb, who is now in the group Chicago and who had also been in the Grace Church Choir. That was my heartland but I respected what I heard. I was carried on by his energy and flattered that he thought of me. At the time I was an owner-operator of a tractor trailer, and the engine had blown up, so it was an easy leap to make. Harry paid me $10 a week. Ron was with us for three and a half years until Harry's Broadway show [The Night That Made America Famous].

Ron thought it was ridiculous that just as "Cat's In The Cradle" had hit number one, Harry had locked himself up for two years with the show when he was about to cash in on concert revenues. Ron was bitter, and we weren't involved in the decision, so he quit. He didn't regret it. Fortunately for Harry's career, the show only lasted 6 weeks (12 with rehearsals). We came out of it with Steve, Tom and Howie Fields. It became a six-piece band with the new configuration, and we started doing concerts again.

Circle!: Can you tell us the story of the first time you appeared in public after "Taxi" hit the radio?

Wallace: It was Banana Fish Park in Brooklyn and Urbana, IL. What a huge difference that made! We'd been doing gigs here and there with polite applause, but it was the first place it was on the radio and people went nuts. Now we're in a whole new level of magnitude. It was really exciting but funny because it was like before, but the only thing different was that people had heard it on the radio. We walked out and people went nuts, and there was a standing ovation, and we hadn't even done anything. We got carried away to a certain extent, but I was 28 and Ron was 36. We were more settled and it would have been worse if we were younger. It was the Mason-Dixon Line back then--on the radio or not on the radio. Of course, "Taxi" made Harry a legit player.

Circle!: Let's go back to the beginning when the band first got together.

Wallace:

The band's first rehearsal was June 22, 1971 in Fred Kewley's

office in Port Chester, New York (Kewley was Harry's manager). Harry

hired Ron over the phone, and I hadn't met any of them before. We

had only a week to get ready and learn seven songs, including "The

Baby Never Cries" and "Could You Put Your Light On, Please?"

but we managed to do it. But I wasn't really a player at that point.

It was tough for me. I had bought a used Fender six months before in a

pawn shop. I had comprehension of it and wanted to play bass but had not

been playing long at all. I was just learning notes and strings. It was

not a fun time with the high pressure. We had to learn the songs, and

I was not confident starting at ground zero.

Harry never lacked confidence. The first time I heard "Cat's In The Cradle" I thought, ‘This song is good.' Harry was standing in front of me with his foot on a chair and banging out chords, and I thought, ‘This is great and this is a hit.' We just went with the program, and not even six months later it was a rocket. After four months we were flying in Elektra's corporate Gulfstream with Holzman himself and recording in Elektra's own studios. We never lost respect in terms of who we were. We were humble and knew we had a lot to be humble about. We got carried away by the trappings but not so much Harry. Harry was more goal-oriented, didn't even smoke cigarettes, no drinking--not involved in that stuff. It was a brutal schedule in those days, but you use whatever help you can. We were doing 20 nights a month at that point. No bus, no limo. We drove or flew and you don't always eat right on the run. We were lucky to get to sleep at three or four in the morning and were up at seven. The lifestyle is important because of what happens to people and bands. You have to work at keeping people together under those circumstances.

Circle!: Is it true that Harry once went 17 days without sleeping in a bed?

Wallace: : During the time he was lobbying Congress, Harry told me he'd leave from a concert and go straight to the airport. He slept in a chair at the airport. He'd fly to DC, lobby, get the last flight out to the next gig and did this for 17 days straight. The Chapins are industrial strength versions. He was intelligent about eating. I never saw him down until the very end. He was always upbeat and positive.

Circle!: I've read about the band squabbles and dissatisfaction and Harry's short-lived attempt at democracy with the band. What kept you there during the tough times?

Wallace: Part of that was fact that it had been the four of us in the band, and after awhile Harry drifted away and rightly so. He had so many things going on, so it was like leaving a cat or dog home alone. It was more like being abandoned. He wasn't ours anymore; he belonged to everybody. Harry never did anything maliciously to cause you grief. If it happened it was inadvertent on his part.

Circle!: This is a good lead-in to the story about Harry overhearing you complaining in the bathroom.

Wallace:

I know the one you mean. Harry had gotten into saying, loudly, "Are

you ready?" to get the audience ready, but it drove us crazy. I thought

let the music talk for itself, but Harry liked his raps. I was complaining

about it in the bathroom. I had a feeling somebody else was in the room,

but nobody was in the stall so I left. The next day Steve said Harry had

been in the bathroom in one of the stalls. Harry didn't want to embarrass

me, and he didn't say anything about it. So it's the next night

and next town, and Harry turned and looked at me and said, "Are you

ready, John?" Nothing else was ever said about it.

Harry never

held a grudge. We loved each other. It was a big brother/father kind of

relationship even though we were only a year apart. Once when I'd

been in the band for eight years, I threw my arms around him and gave

him a big kiss and said, "I want to thank you for best eight years

of my life." Harry was embarrassed, uncomfortable, but he knew and

just didn't want to hear it. We fought amongst ourselves. Doug and

I would argue every six weeks or so. It was so regular you could set your

watch by it. Doug's a special person and great guitar player.

Most of the time it went smoothly, and we'd only grumble about how long the shows were. You needed a hook to get Harry off the stage. One two-show night was infamous. At the Valley Forge Music Fair they have to clear the parking lot between shows. Harry didn't want to stop and each show was over four hours long. It was exasperation not anger. There were no major fights or catastrophes.

|

|

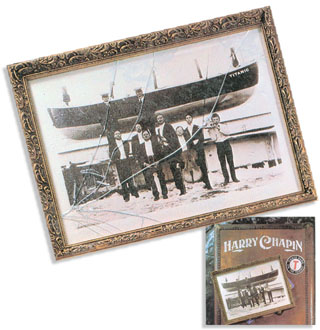

The

Dance Band on The Titanic CD can be ordered

through the Chapin family's official site at harrychapinmusic.com. |

Circle!: Tell us about shooting the cover of the "Dance Band On The Titanic" album.

Wallace: That was fun down at the South Street Seaport on a schooner. It was 30 degrees in January, and the deck was covered in snow. First they wanted the deck to be clear so we were shoveling the snow, and I think then they decided they wanted the snow on there after all. We were in tuxes and nothing else. I still remember how cold it was. I think you can see it if you look at the picture. I also remember "Dance Band" for the opportunity to play with the great drummer Steve Gadd. He's so good that Paul Simon keeps him on retainer to play whenever he needs him.

Circle!: Much of what we do in "Circle!" is try to inspire Harry's fans and others to act on his call to "Do something." Tell us about Harry's transition from star to citizen activist and how you felt about doing so many benefit concerts.

Wallace:

It wasn't a transition. Harry came from the tradition of Pete Seeger and

Woody Guthrie. His family was staunchly liberal and even radical. Their

currency wasn't dollars; it was achievement. They were the Brooklyn Kennedys

without the money. They had a desire for excellence and achievement and

contribution to society. He was concerned about making people's lives

better. Success gave him entrée and legitimacy to meet people and

to get involved and have an influence. It was probably his goal from the

beginning. To get him satisfied he would have liked to be President, have

an album and book in the top ten and do a show, all at once if possible.

He couldn't have too much achievement. It was not for the money; it meant

nothing to him. He didn't care at all for the trappings of success, just

the power.

At first

Harry announced we'd be doing 24 concerts a year as benefits. I didn't

jump up and down about it. We were resigned and it was going to good cause.

We were slightly annoyed that it was a decision handed to us. It was a

pretty big chunk, 20 percent of what we were doing, to be giving up. He

didn't take anything. It wasn't like giving it away after expenses.

He'd give a whole check, so it was really a lot more with travel

expenses and whatnot. Nobody gave him grief about it.

Circle!:

You continue to perform at benefits for hunger-related organizations such

as Long Island Cares, World Hunger Year, LUNCH and John McMenamin's annual

Remembering Harry Chapin concert events. What keeps you motivated to continue

lending your talent to these causes?

Wallace:

I just do it. If I'm not going to be involved in Chapin stuff, who

is? I feel like an honorary Chapin, and the connection goes so far back

so I've got to be here through it all.

Circle!:

I have to ask about Last Stand. In our Summer issue, Howard Fields talked

about the day Harry wrote that song in response to the shooting of President

Ronald Reagan. He recalled that Harry said eventually you'd be singing

it. What do you suppose Harry meant by that? Did you sense that Harry

truly believed he was not destined to live to a normal life span? What

did it mean for you to sing it at the Carnegie Hall tribute?

Wallace:

Looking back on it you can ascribe more in hindsight. He burned the candle

at both ends with no regard to normal creature comforts and sleep. It's

easy to say it's as though he knew only half a life to live must burn

twice as brightly. He was bringing in new songs at rehearsal. He said,

"You're gonna sing this one on next album." When I sing it I wonder. It

was all right because who was going to communicate his songs better than

he was?

Carnegie Hall was pretty intense. I wasn't in music at the time. The Steve Chapin Band hadn't started. I was not in a good place, trying to fight my way back to life. It's something I'll keep with me. I like the song; it's powerful and part of his legacy. I always hated everything I did and didn't want to listen to it until years had passed. I felt I got better as the years went on. I was never that comfortable; it was not fun to be on stage, but I do it and keep getting through it.

Circle!:

You were the singing voice of Bluto in the movie Popeye. How did

that role come about?

Wallace:

Harry got it for me. Somehow he talked to someone. He said, ‘Hey,

you want to go do a voiceover for [film director] Robert Altman? It paid

$750 and was fun, and I got to meet him. I walked into his office with

the big, beautiful desk and said, "…nice slab of plywood." His associates

look around at each other to see if it was okay to laugh. They gave me

a scotch and acted like it was a big deal. Altman was very nice and charming

and spent a lot of time with me. I showed up the next morning, and it

was up on a screen. I had to sync the music with the video. I did a few

takes but didn't have a good bass voice that day. Did it and that was

it.

Once I did

a Dentyne commercial for Steve's commercial company. I played bass

and sang, "Ooh ooh wah" and was paid $90,000.

Circle!:

Aside from appearing with the Steve Chapin Band, what are you doing professionally

now?

Wallace:

I've been working at a publishing company for six years as an art director.

I do layout of editorial content and place ads for three periodicals.

Circle!:

I understand that we share the opinion that "Sniper" is Harry's masterpiece.

Can you tell me about recording it?

Wallace:

: We learned that song in pieces in the studio, and it was so big we couldn't

learn it all at once. Remember, Sniper was just our second LP. We tried

to do it and would take it one second at a time. It's music first

for me. Words are like placeholders. There's a lot to think about

on stage, and then I get lost in it and become part of it.

Circle!:

Perhaps the most unique and distinctive component of Harry's band is the

cello. Why was it important for Harry to include that in his music?

Wallace:

He always thought about James Taylor's "Fire And Rain." Actually, that

was an acoustic bass played with a bow. He heard that sound and felt his

voice was rough, masculine, and he wanted a softer, more feminine, sound

to counter-balance it. He knew in beginning he wanted it there.

Circle!:

Can you share some of your favorite memories of Harry that most of us

have not heard before?

Wallace:

It would be some of the times we'd play his songs in living rooms in Brooklyn

Heights. We spent a fair amount of time together in beginning before college.

Harry would bring his songs over and play them for me and ask what I thought.

He was a young writer polishing his craft. Being together and sharing

this was a special time for me.

I remember Harry's first awareness, consciousness, of what we ate. Elektra's offices were in the Gulf and Western Building in New York. This was when ingredients labels first came on stuff. Harry had a fondness for Cool and Creamy, an imitation topping. We were in the drugstore downstairs, and he was reading the list of ingredients, a long paragraph of chemicals. And he said, "This shit would give cancer to rocks."

Circle!:

There has been some confusion about who sings the part of "Bluesman."

Can you please clear that up?

Wallace:

Harry sings the part of the narrator, and I sing the part of the bluesman.

Circle!:

As our final question I have to ask if you can you tell us how Harry came

to use "O Holy Night" for the part you sing as "Mr. Tanner"?

Wallace:

It was spliced together because it was operatic, and Harry knew it from

Grace Church. It came from a review he read about Martin Turbidy and is

the actual review. He could identify with putting his soul on the line

to be accepted and loved and putting it all out there, but what a downer

a bad review would be.

When I'm singing one of Harry's songs, I'm really concentrating on making the part good, singing the best I can in that situation at that time. I'm trying to make that play and am totally focused on singing the best I can. Every song that comes up I try to lock it in and get to point where I'm beyond the fact of thinking about it. I started climbing it and never got there during the time with Harry. With Steve occasionally I'd get to that place where it's flowing and pouring out of you.

Watch for the Next Issue of Circle! on March 7